Oppenheimer: The “Santa Claus Market” in US stocks has arrived, and the “January effect” can be expected!

The Zhitong Finance App learned that the “Santa Claus Market” from December 24 to January 5 has always brought rich returns to investors. Since 1928, the S&P 500 index has risen by an average of 1.6% during this period. Over the past 97 years, the probability of the index rising in these seven days was as high as 77% (75 years). Ari H. Wald, head of technical analysis at Oppenheimer, pointed out that this performance is in stark contrast to any typical seven-day cycle, where the average increase was only 0.2% and the probability of increase was 57%. Also, when the “Santa Claus Market” fails to appear, the performance for the next one to two quarters is often below average.

Wald said, “Since 1928, after experiencing a falling Christmas market, the S&P 500 index fell by an average of 1% over the next three months, and after experiencing a rise in the Christmas market, it rose by an average of 2.6% over the next three months.” He also quoted an old Wall Street saying, “If Santa doesn't come, a bear market may be coming.”

Looking ahead to January, Oppenheimer analysts have found some encouraging signals based on the index's position relative to its 200-day moving average. Since 1950, when the S&P 500 opened above its smooth trend line in January, it had an average increase of 1.2%, with a probability of increase of 64%; while when the opening price was lower than this trend line, it had an average increase of 0.7%, with a probability of increase of 50%. Currently, the index is above this critical technical level.

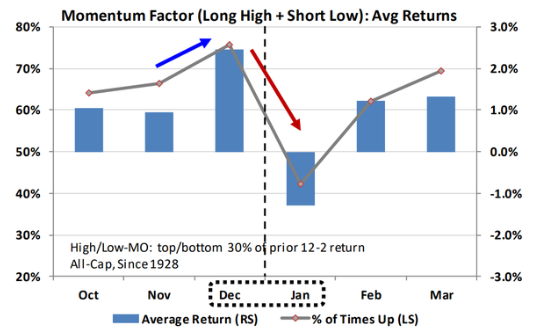

Furthermore, the January Momentum Factor (SPMO) has been the worst performing month of the year. The factor tracks the performance of market leaders and laggards over the past 12 months. The excellent performance in December usually reflects a tax deduction strategy, where investors sell loss-making stocks to offset capital gains taxes. This makes January the worst performing month for momentum strategies because “stocks that did not perform well in the previous year are then bought back”. This is the so-called “January effect.”

In other words, according to a popular theory, the US stock market often rose more in January than in other months. This phenomenon is known as the “January effect” because research shows that January's increase was several times the average for other months. This impact was most evident in small company stocks from 1940 to the mid-1970s. However, around 2000, this increase seemed to have shrunk, and since then it has been less reliable.

The “January effect” was so widely accepted decades ago that most research has focused on trying to find the nuances and causes without coming to any definitive conclusion. But there are other theories. The main theory is that in December, many individual investors made tax-loss savings (Tax-Loss Savings) of investments, that is, selling off loss-making positions to offset profits, thereby reducing tax liabilities. The theory suggests that after January 1, investors will stop selling and supplement their stock portfolios, thereby driving up the stock market. Another theory is behavioral theory: people make financial decisions at the beginning of the new year and adjust investments accordingly, thereby boosting the stock market. Many high-paying investors rely heavily on year-end bonuses, which give them plenty of cash to invest at the beginning of the new year.

Nasdaq

Nasdaq Wall Street Journal

Wall Street Journal