South Korea is caught in an exchange rate defense war: trillions of retail funds are flocking overseas, and national pensions are forced to sell dollars

The Zhitong Finance App notes that the South Korean authorities are taking increasingly aggressive actions to try to stop the Korean won exchange rate from falling to a new low since the deep global financial crisis in early 2009.

To support the won, officials pressured the country's pension fund to sell dollars and urged a huge group of “chaebol” to exchange more dollar earnings back into the local currency. Currently, these measures have not been able to contain the exchange rate decline.

A weak currency is two-sided for South Korea because it enhances the competitiveness of exports, which are the main driving force in this $1.9 trillion economy. But it will also cause the price of energy and other key imported commodities to rise, disrupt commercial investment, and depress consumer demand.

What is weakening the won?

The government said one reason was the sharp increase in overseas investment by local residents. According to data from the Korea Securities Registration and Clearing House, as of December 19, Korean retail investors have purchased a record $43 billion (approximately 63.7 trillion won) of US assets this year, with US stock purchases approximately three times the level for the full year of 2024.

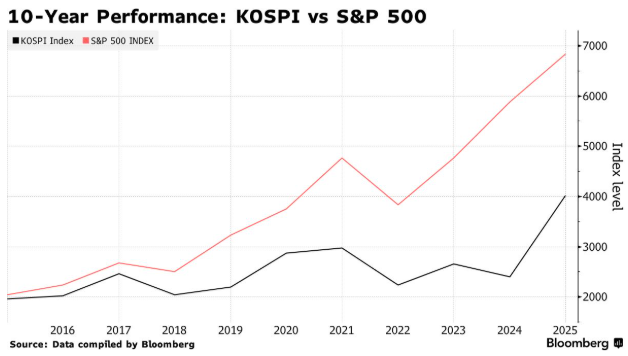

Government officials also mentioned South Korea's slower economic growth and lower interest rates compared to the US, considering that accusing the public of causing currency depreciation may trigger negative public opinion. Central Bank Governor Lee Chang-yong pointed out the enduring “Korean discount” phenomenon — that is, the value of the country's top chaebol and overall stock market has been undervalued for a long time due to corporate governance issues.

Since September, broader macroeconomic factors have indeed been unfavorable to the won: expectations of the Federal Reserve's interest rate cut have subsided; South Korea agreed to establish a $350 billion investment fund in tariff negotiations with the US, weakening demand for the Korean won; furthermore, neighboring Japan's yen has continued to weaken under the new Conservative government.

However, large-scale overseas investment by South Korean residents continues. As the end of the year approaches, foreign investment, which had been steadily buying Korean stocks until now, has turned into net sales, which further intensified the pressure on the won.

Why do Koreans keep sending money overseas?

The lackluster returns of Korean stocks over the years have convinced many savers that the domestic stock market cannot provide reliable long-term returns. As a result, they transferred funds abroad. Older Koreans are particularly wary of excessive reliance on domestic investment, as they still have fresh memories of the Asian financial crisis that swept through the nation's wealth in 1997.

High housing prices in South Korea (especially in the capital Seoul) are another factor. Many young homebuyers now feel cut off from the housing market. Instead of saving money for a down payment on a property, they are investing their savings in high-risk overseas investments and cryptocurrencies as a way to maintain hope for upward liquidity.

This trend is somewhat characterized by “self-actualization”: retail investors told the media that they are moving assets overseas to protect themselves from the depreciation of the won. Technical factors also played a role. Since the pandemic, the threshold for individuals to enter foreign investment platforms and purchase related products has been drastically lowered.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of the weak won?

For the export-oriented Korean economy, depreciation of the local currency is indeed beneficial. Thanks to strong earnings and favorable exchange rates in the US, companies such as Samsung Electronics have repeatedly set profit records over the years.

However, the weakening of the Korean won will also cause import prices to rise, and South Korea relies on imports for most of its energy, which poses a risk. The central bank warned that the continued weakness of the won could push inflation higher than the target level.

The won depreciated by half during the 1997 crisis and faced selling pressure again during the 2008 global financial crisis. Since then, the South Korean authorities have been wary of extreme exchange rate fluctuations that may be triggered by global capital flows. The current plight of the Korean won may complicate South Korea's efforts to open the foreign exchange market around the clock and to be included in the MSCI developed markets index.

How are the South Korean authorities trying to boost the won?

Government officials have issued verbal warnings in recent weeks against so-called “unilateral market fluctuations.” But these warnings didn't stop the exchange rate from approaching its lowest point since 2009. As a result, the authorities have stepped up efforts to seek cooperation from major domestic players in the foreign exchange market.

The Korean National Pension Service (NPS), which holds about $542 billion in foreign assets as of the end of September, extended the foreign exchange swap agreement with the Bank of Korea and announced that it will adopt a more flexible currency hedging strategy.

According to people familiar with the matter, a senior government official summoned the heads of the seven major Korean champions, including Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix, to ask for their cooperation to avoid the public's negative perception that these powerful companies are profiting from currency fluctuations during a period of extreme market sensitivity.

The government has also relaxed foreign exchange market stability rules to ensure the liquidity of the US dollar. Financial regulators are concerned about excessive competition among companies providing overseas brokerage services, prompting brokers to stop new marketing activities related to foreign stock trading.

The authorities continued to carry out “smooth operations” to deal with the currency's unilateral trend, but did not directly intervene on a large scale that could exhaust foreign exchange reserves. A central bank official told the media that foreign exchange authorities do not set specific exchange rate targets, but will step in when price fluctuations become excessively intense.

Why are the measures not working?

Because this round of weakening of the won is driven by continued overseas investment by South Korean residents, this trend is not easy to reverse.

Authorities face balance problems when trying to support the exchange rate by putting pressure on domestic institutions and adjusting their monetary strategies. If the National Pension Service (NPS) actually increases safe-haven hedging on a large scale, the won may rebound faster than current market expectations — and this itself will bring a new set of risks.

Nasdaq

Nasdaq Wall Street Journal

Wall Street Journal