The Bank of Japan raised interest rates this week without any suspense. The market fully included expectations of another rate hike before October next year

The Zhitong Finance App learned that Bank of Japan Governor Ueda Kazuo is expected to raise the benchmark interest rate to the highest level in 30 years this Friday, but between the government's dependence on low-cost financing and the weakening yen driving up import inflation, the future policy path is becoming more and more complicated.

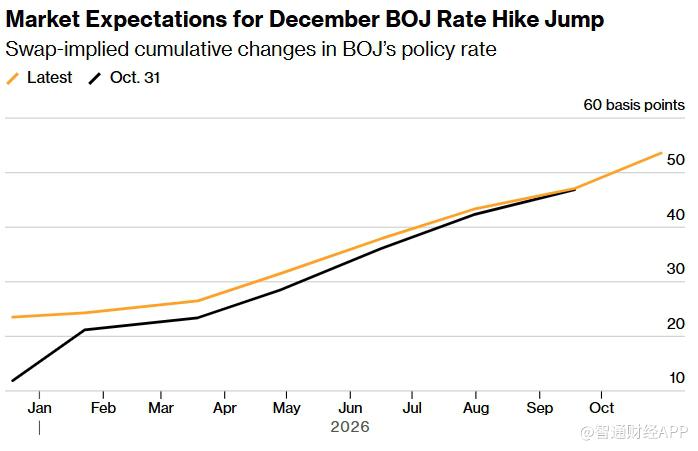

The market generally expects the Bank of Japan to raise the policy interest rate by 25 basis points to 0.75% at the end of the two-day monetary policy meeting. This is the first time since Ueda took office that the economists interviewed agreed to expect interest rate hikes. According to a media survey, all 50 economists interviewed expected this rate hike, and overnight index swap (OIS) pricing also showed that the probability of interest rate hikes this week has risen to more than 90%, almost doubling from the end of October. At the same time, the market has fully taken into account expectations of another rate hike before October 2026.

In the context of this rate hike, Japan's new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, is in a particularly delicate situation. The first female prime minister in Japanese history described the “interest rate hike” as a “foolish act” last year, but under the actual pressure of rising living costs, inflation eroding people's purchasing power, and falling approval ratings from the ruling party, she has avoided publicly criticizing Ueda's plan to gradually withdraw from ultra-loose policies since taking office in October last year, and has instead focused her policy on containing inflation.

However, the Takaichi government also needs to prevent treasury bond yields from rising too fast. The Japanese government is preparing a budget for the next fiscal year, which is usually announced in late December. The yield on Japan's 10-year treasury bonds once rose to 1.97% this month, hitting an 18-year high, prompting Ueda to publicly warn last week that the rate of increase in yield was “slightly faster.”

Analysts pointed out that the last time the Bank of Japan's benchmark interest rate was close to the current level, the yield on long-term treasury bonds was around 3%. If the yield approaches this level again, it will significantly push up interest expenses, put more fiscal pressure on the Japanese government, which bears the highest public debt burden among developed countries, and limit its policy space to mitigate the cost of living crisis while increasing defense spending to meet regional security challenges.

Ryutaro Kono, Japan's chief economist at BNP Paribas, said that considering that the high city government favors a low interest rate environment, it is expected that the Bank of Japan will keep the pace of interest rate hikes relatively restrained in the future and may maintain a frequency of roughly every six months. But at the same time, he warned that if exchange rate fluctuations increase, the risk that the central bank will be forced to speed up policy tightening is not small.

If interest rate hikes are implemented this week, this will reinforce the Bank of Japan's “heterogeneous” position as the only major central bank still raising interest rates this year. This will also be the first time since the Bank of Japan adopted the current meeting system in 1998 that it and the Federal Reserve have adjusted interest rates in the opposite direction within the same month. Shigeto Nagai, the former head of the Bank of Japan's International Affairs Bureau, said that with frequent changes this year, it may still face more turbulence in the future. “If Ueda continues to raise interest rates, it is already considered lucky.”

As the market fully anticipates interest rate hikes, investors' focus will shift to Ueda's forward-looking guidance at the press conference. Economic research points out that Ueda is expected to maintain careful wording to avoid clearly hinting at a specific schedule for future interest rate hikes.

It is worth noting that the Bank of Japan does not believe that the so-called “neutral interest rate” has already been reached by raising the convenience rate to 0.75%. According to people familiar with the matter, some officials believe that even if it rises to 1%, the policy stance may still be relaxed. This suggests that while inflation continues to be high, there is no room for further interest rate hikes.

Japan's core inflation index has remained at or above the central bank's target level of 2% for three and a half years, the longest record since 1992. The weakening yen played a key role in this, with companies passing on higher import costs to consumers and driving up prices. Currently, the yen is hovering around 155 against the US dollar, close to the level that forced Japan's Ministry of Finance to intervene four times in the market last year. Finance Minister Katayama recently made a rare statement in May that intervention in the foreign exchange market is still an option, highlighting that official dissatisfaction with the weak yen is heating up.

At the same time, US Treasury Secretary Bessent also put forward opinions on the direction of Japan's policy. He once said that the Japanese government should give priority to allowing the central bank to deal with inflation through interest rate hikes, then consider directly interfering in the foreign exchange market, and bluntly stated that the Bank of Japan is “slow to act” in dealing with inflation.

Even if interest rate hikes are implemented this week, the Bank of Japan's policy interest rate will still be only higher than Switzerland's among major central banks, ranking second to last. Hideo Hayakawa, the former executive director and chief economist of the Bank of Japan, believes that if domestic political changes and US President Trump's aggressive tariff policy were not a threat to Japanese exports, Ueda might have taken further interest rate hikes sooner. “This was an unlucky year for the Bank of Japan. Against the dual backdrop of Trump and high markets, the Bank of Japan's policy pace was forced to lag behind the situation.”

Nasdaq

Nasdaq Wall Street Journal

Wall Street Journal