When diversification lost to a technology stock concentration frenzy, active funds faced a trillion-dollar redemption wave

The Zhitong Finance App learned that for diversified fund managers, there is nothing more difficult than managing portfolios that are highly dominated by seven technology companies — all of them are US companies, all with huge market capitalization, and all focus on the same sector of the economy. However, just as the S&P 500 index once again reached an all-time high this week, investors had to face a harsh reality: if they want to keep up with the pace of the market, this largely means being forced to take heavy positions in these stocks.

In 2025, a small group of closely linked tech supergiants once again contributed a disproportionate return — a pattern that has continued for almost a decade. What is really noteworthy is that it's not that the familiar winners list is still the same, but that this income gap is at an unprecedented intensity, seriously testing the bottom line of investors' patience.

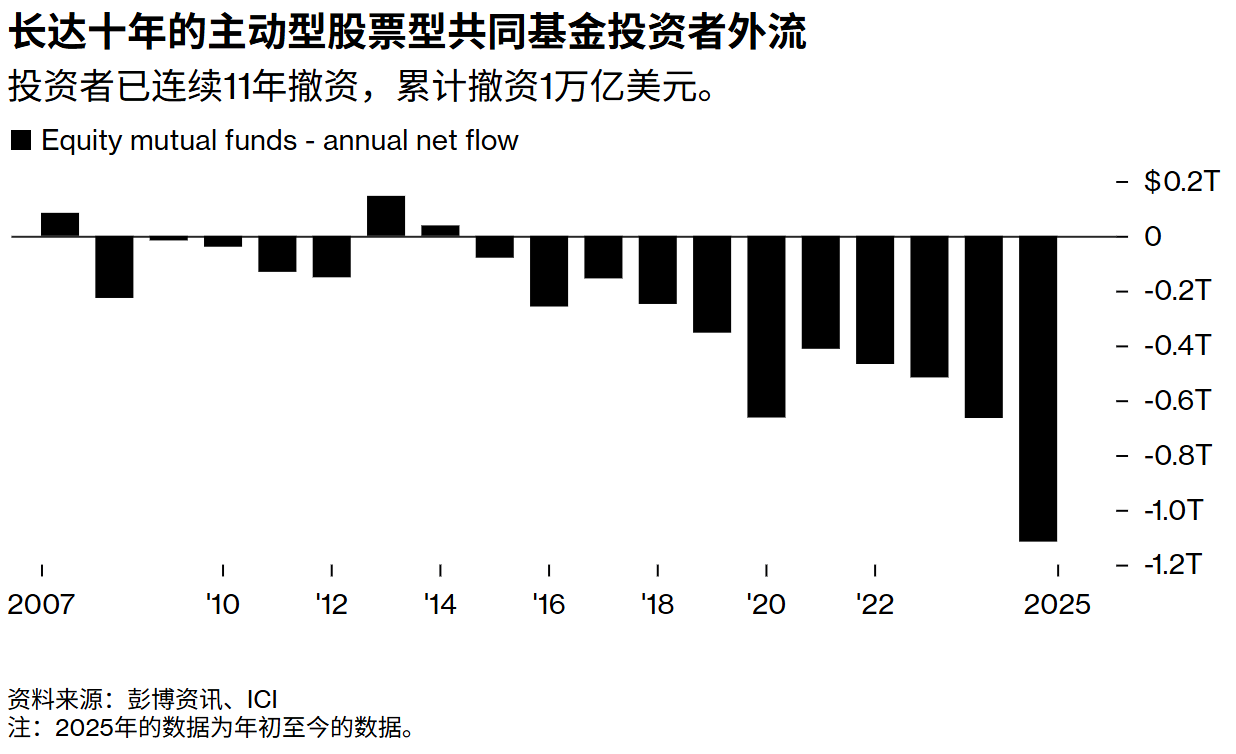

Frustration determines the flow of money. According to data estimates from the American Association of Investment Companies (ICI), about 1 trillion US dollars flowed out of active stock mutual funds throughout the year, marking the 11th consecutive year of net outflow, and measured by certain indicators, it was the worst outflow in the current cycle. In contrast, passive stock exchange traded funds (ETFs) received more than $600 billion in capital inflows.

Figure 1

As the year progressed, investors began to gradually withdraw — they re-examined whether it was worth paying the extra cost of a portfolio that deviated significantly from the index. However, after review and verification, it was discovered that this differentiated layout not only did not bring the expected return, but instead forced them to face the embarrassing situation of “paying a premium but not receiving benefits”, and in the end, they were only able to passively endure the consequences of the strategy's failure.

Dave Mazza (Dave Mazza), CEO of Roundhill Investments, said, “This centralization makes it harder for active fund managers to achieve good results. If you don't allocate the 'Big Seven' according to the benchmark weight, you are likely to run the risk of losing.”

Contrary to commentators who thought they could see stock selections shine, the cost of deviating from the benchmark was still prohibitively high this year.

The upward surface is narrow

According to data compiled by Bank of New York Investment Corporation, in the first half of this year, stocks rose at the same time as the general market during many trading days by less than one-fifth. A narrow rise in itself is not unusual, but its continued existence is the key. When gains are repeatedly driven by very few stocks, diversification no longer contributes to relative performance; instead, it begins to drag down performance.

The same phenomenon is also reflected at the exponential level. Looking at the full year, the S&P 500 performed better than its weighted version, which gave equal weight to a small retailer and Apple (AAPL.US).

For investors evaluating active strategies, this has become a simple arithmetic problem: either choose a strategy with a low allocation of large-cap stocks and take the risk of falling behind; or choose a strategy close to index weight allocation, yet it is difficult to prove that it is reasonable to pay for this method, which is not much different from passive funds.

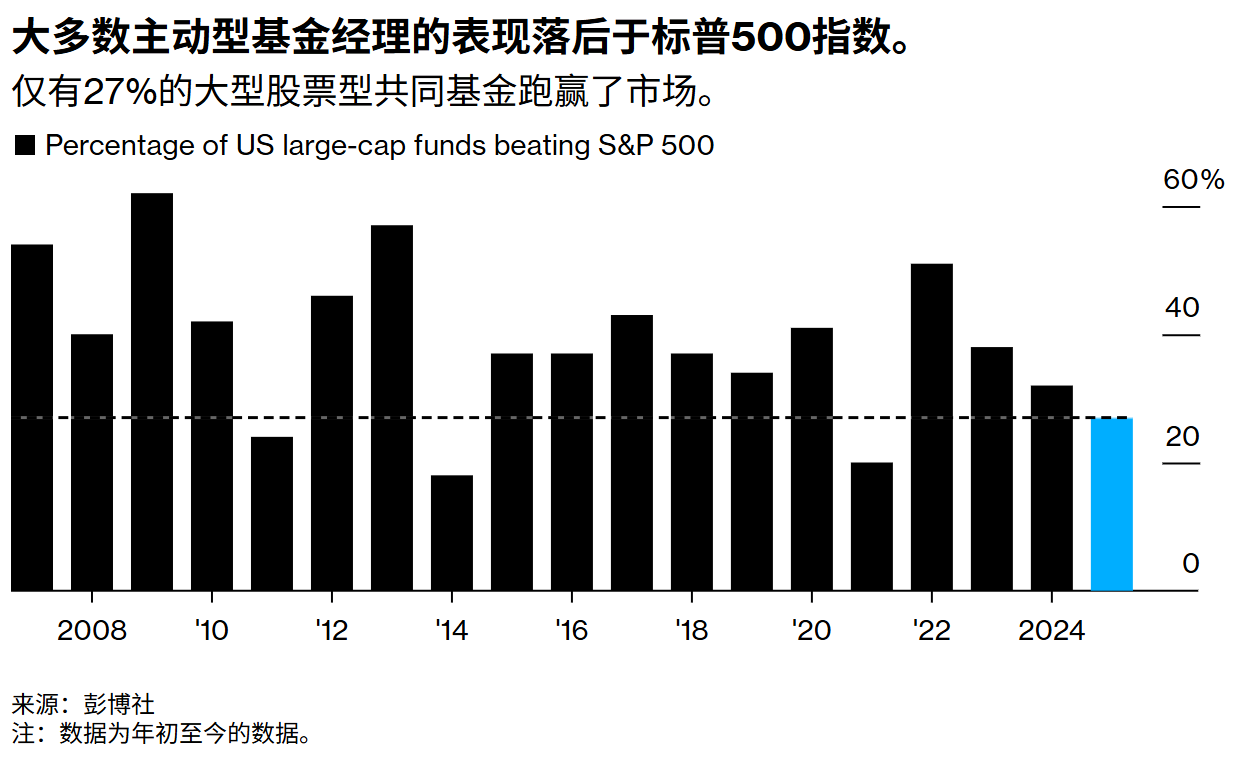

According to public data, up to 73% of products in US equity mutual funds outperformed the benchmark index in 2025, and this ratio hit the fourth highest since 2007. Especially during the market rebound triggered by the tariff scare in April, this failure phenomenon was further intensified — continued fanaticism about the artificial intelligence industry continued to strengthen the leading edge of technology stocks.

Figure 2

There are exceptions, of course, but these exceptions require investors to accept very different risks. One of the most notable examples comes from the Dimensional Fund Advisors LP, whose $14 billion international small-cap value portfolio returned just over 50% this year, not only outperforming the benchmark, but also surpassing the S&P 500 and NASDAQ 100 indices.

The structure of this portfolio is quite revealing. It holds around 1,800 stocks, almost all of which are located outside the US, and is heavily involved in the financial, industrial, and materials sectors. Instead of trying to bypass the US large-cap index, it's more like stepping out of it.

Joel Schneider (Joel Schneider), the company's associate head of portfolio management in North America, said, “This year taught us a great lesson. Everyone knows that diversified investments around the world make sense, but it's hard to actually stick to it. Chasing yesterday's winners is not the right strategy.”

Hold on to the winner

Margie Patel (Margie Patel), fund manager of Allspring Diversified Capital Builder Fund, is an example of holding on to the faith. The fund's return this year was around 20%, thanks to bets on chipmakers Micron Technology (MU.US) and AMD (AMD.US).

“A lot of people like hidden or quasi-indexed investments,” Patel said. Even if they aren't sure they can outperform, they want to have configurations in every sector.” In contrast, her opinion is: “Winners will keep winning.”

The trend of larger capitalization stocks is increasing, making 2025 a good harvest year for potential bubble hunters. The price-earnings ratio of the Nasdaq 100 Index is more than 30 times, and the price-sales ratio is about 6 times, all at or close to historical highs. Wade Bush Securities analyst Dan Ives (Dan Ives) launched an ETF (code IVES) focused on artificial intelligence in 2025, which has rapidly expanded to nearly 1 billion US dollars. He said that this kind of valuation may make people nervous, but it is definitely not a reason to abandon this topic.

“There will be moments where people sweat, but it is these moments that create opportunities,” he said in an interview. “We think this tech bull market will continue for another two years. The key for us is to identify indirect beneficiaries, and this is how we continue to deal with the Fourth Industrial Revolution from an investment perspective.”

Thematic investments

Other success stories have benefited from another form of concentrated investment. The VanEck Global Resources Fund returned close to 40% this year, benefiting from demand related to alternative energy, agriculture, and basic metals. The fund was founded in 2006 and owns companies such as Shell (SHEL.US), ExxonMobil (XOM.US), and Barrick Mining (B.US). The management team includes geologists, engineers, and financial analysts.

“As an active fund manager, this allows you to chase big topics,” said Shawn Reynolds (Shawn Reynolds), a geologist who has managed the fund for 15 years. But this approach also requires firm conviction and tolerance for volatility — after years of unstable performance, many investors are less interested in these qualities than before.

Figure 3

By the end of 2025, the core lesson investors learned was not “active management failed” or “indexed investment has solved all market problems”. The lesson is simpler, yet more disturbing — after another year of concentrated increases in technology stocks, the costs of deviating from mainstream strategies are still heavy. For many investors, the will to continue to pay premium costs for “non-mainstream layouts” has declined significantly from previous years.

However, Goldman Ali of Goldman Sachs Asset Management believes that in addition to large technology stocks, there are still “alphas” to be found. The co-head of global quantitative investment strategy relies on the company's proprietary model, which ranks and analyzes approximately 15,000 global stocks on a daily basis. The system, built around the team's investment philosophy, has helped its international large-cap stocks, international small-cap stocks, and tax management funds achieve a total return of about 40%.

He said, “The market will always give you something; you just need to observe in a very calm, data-driven manner.”

Nasdaq

Nasdaq 華爾街日報

華爾街日報