The “canary” of the global bond market! Will pressurized Japanese treasury bonds be the “first domino” to fall?

As yields rise and the Bank of Japan gradually halts bond purchases, Japan faces the dual challenges of structural debt and inflation. Higher yields on Japanese treasury bonds could disrupt the global bond market, and potential capital outflows could affect US Treasury bonds. Japan's ability to repay its debts through inflation is constrained by slow real economic growth and an aging population, which has raised concerns about a resurgence of financial restraint. Despite weak currencies and rising yields, the Japanese stock market and gold (in yen) performed well, reflecting the repricing of global assets and governments seeking to reduce debt through inflation.

The Japanese bond yield and yen exchange rate tend to rise

Japan has been in an environment of near-zero interest rates, curbed volatility, and chronic deflation for decades, but this has rapidly changed. In addition to the cancellation of the Japanese yen arbitrage deal, Japan's problems are structural debt and inflation, which may soon plague other developed markets, including the US. Japan may be the first domino to fall.

Japan's entire fiscal and monetary system is based on the assumption that interest rates are permanently low, and this monetary experiment may be coming to an end — Japan's treasury bond yields are rising. Some investors believe that if Japanese bond yields fully converge with or even surpass US bond yields, it could “destroy” the global bond market.

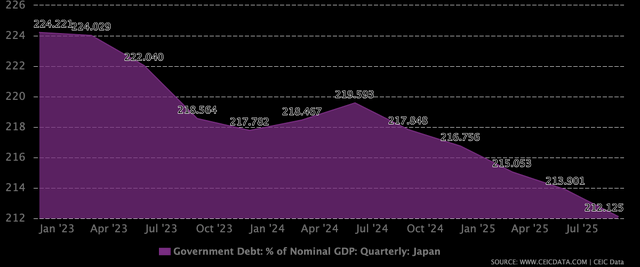

Japan's debt accounts for more than 200% of GDP, while America's debt accounts for nearly 120% of GDP. Both numbers are historically high and problematic, and the difference in scale is critical. The government uses tax revenue generated by the economy to repay debts. When debt grows much faster than economic output, even a small rise in interest rates may exceed fiscal sustainability. In Japan, for example, a large portion of the government's annual expenditure is already used to repay debts. Higher yields will soon crowd out all other expenses. This is likely to further boost Japanese bond yields.

For more than 20 years, Japan has been plagued by deflation. This enabled the government to borrow on a large scale at extremely low interest rates, with few immediate consequences. Today, the macroeconomic context has changed. Over the past three years, Japan's average inflation rate has been around 3%. While this number may seem small compared to recent experiences in the US or Europe, it is a profound shift for Japan. Low inflation made aggressive monetary easing safe, and eventually became the core of today's famous Japanese yen arbitrage transactions.

Can Japan get out of debt through economic growth?

This is the key question. There is reason to believe that Japan can reduce the debt burden caused by inflation by increasing its nominal GDP, but the country is also facing some challenges. Since the vast majority of Japan's debt is denominated in yen and held domestically, Japanese policymakers have more control than countries that rely on foreign capital.

If the inflation rate can be maintained within the range of 2% to 3%, nominal GDP growth will rise, tax revenue will increase, and the real value of existing debt will gradually decline. However, due to an aging population, weak productivity growth, and limited immigration, Japan's structural growth has been slow. Inflation without real economic growth is likely to drive up costs without significantly expanding the tax base.

Meanwhile, rising bond yields threaten the entire strategy. Japan can only get out of trouble through inflation, provided that interest rates remain below the nominal growth rate, and the market is currently reacting to this. If the yield rises too high, it may lead to the introduction of a policy to suppress yield again. The Bank of Japan may start buying bonds again, and may even require commercial banks to assume more sovereign debt.

Why is this important to America and the world at large?

Some investors believe that if Japanese bond yields fully converge with or even surpass US bond yields, it could “destroy” the global bond market. Although estimates of the scale of Japanese arbitrage trading vary, it is generally believed that it is at least 500 billion US dollars, and this seems to have provided strong support for the rise in global financial markets. If positions are liquidated, it will inevitably have an impact on the global financial market.

This matter is critical for the US and US investors for two main reasons. Japan is the largest buyer of US Treasury bonds, holding over $1 trillion. Instability in the Japanese bond market is likely to spread to the US market. In other words, rising yields on Japanese treasury bonds may encourage domestic investors to return capital to the country, sell US treasury bonds, and buy Japanese treasury bonds. However, as the “anchor of asset pricing,” US bond yields will inevitably have an impact on the global market if it soars.

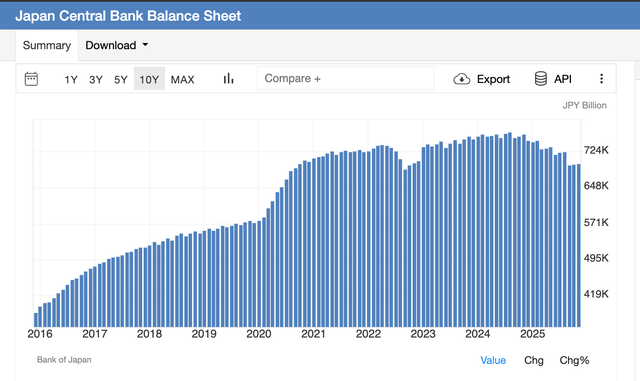

Over the years, the Bank of Japan has played the role of the last buyer of Japanese treasury bonds, reducing yields through large-scale quantitative easing policies. At its peak, the Bank of Japan held an astonishing share of Japanese treasury bonds. Once inflation occurs, this strategy is unsustainable, and the yen in particular begins to depreciate.

Printing money to buy bonds in an inflationary environment poses the risk of currency instability and loss of market confidence. As a result, the Bank of Japan was forced to tighten its monetary policy, and recently even reduced the size of its balance sheet. Logically, when the biggest buyers exit the market, prices fall and yields rise.

What's interesting, though, is that even with higher yields, the Nikkei index outperforms the S&P 500 index. On the one hand, inflation has actually stimulated the Japanese economy, and people hope that wages and incomes will begin to grow. Of course, as the yen continues to depreciate, earnings will increase, at least in nominal terms. That's why, ultimately, when the world's governments try to get rid of debt, whether hard or financial, they perform well.

But perhaps more importantly, Japan has basically shown what America's future might look like. Although America's debt burden is not that heavy, the deficit is still a problem, and the US government will try to reduce the debt burden through inflation. Japan will become “patient zero” because it is trying to do this.

Nasdaq

Nasdaq 華爾街日報

華爾街日報