Daliola sounded the highest alarm: Will America's “debt heart disease” or a trillion-dollar interest attack by 2029 trigger a systemic crisis?

Bridgewater Fund founder and billionaire investor Ray Dalio is increasingly concerned about the sustainability of US debt. Earlier this year, in an interview, he mentioned that the US may have a debt crisis within 2-4 years, that is, between 2027 and 2029.

In this article, I'll show you how his predictions are slowly becoming out of date and what led him to such negative conclusions about the US economy. I'll state my views on every point I'm about to discuss.

The biggest problem with the US economy

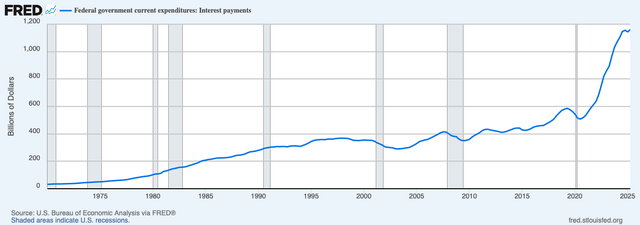

Dario pointed out that the biggest problem with the US economy is its debt burden: the US government has to pay about 1 trillion US dollars in interest every year. Without this interest expense, they will spend 1 trillion more dollars, and the situation will get worse as time goes by. In addition, they also have to roll over the debt they have accumulated before, so this year they will roll over about 9 trillion US dollars, which is slightly more than 9 trillion US dollars of debt. This means that once their newly acquired capital is used up, they will have to sell the bonds again. This becomes a problem when the debt is huge.

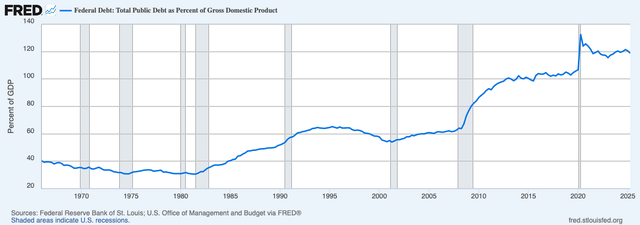

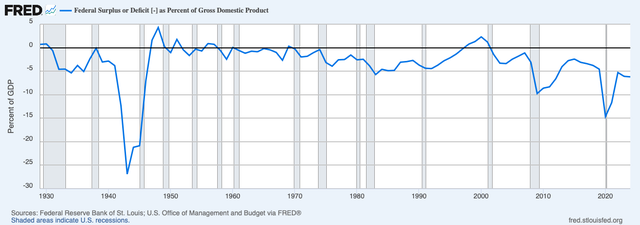

The financial crisis was a turning point in debt sustainability. The crisis was so severe that the Federal Reserve began implementing unconventional monetary policies, such as quantitative easing, which are already common in regions with sluggish economies such as Japan. Interest rates could not be lowered any further, and at the same time, the government began to run a huge fiscal deficit.

These choices proved right. The US economy began to grow rapidly, and the stock market completely recovered its lost ground in just a few years. However, a huge problem followed: the economy became dependent on fiscal expansion and low interest rates. The COVID-19 pandemic was a turning point: fiscal expansion was on a scale comparable to that of a world war.

Although the pandemic is over, the US fiscal deficit remains between 5% and 7% of GDP, far above the long-term average of 2.53% (1947—2024). And interest rates are no longer close to 0%. As Dario said, this new macroeconomic crisis is having a snowball effect on debt. Trillions of dollars of maturing debt need to be refunded (interest rates are higher). Coupled with huge annual fiscal deficits, the interest expenses that the government must pay are accumulating.

Over the past five years, the size of US debt has increased dramatically by about 600 billion US dollars. Interest expenses currently exceed $1.1 trillion, and this money could have been used for more productive purposes (such as investing in education, infrastructure, etc.).

Since the US government has no plans to reduce the debt burden, interest rates are bound to continue to rise. Dario is deeply concerned about this and believes it could trigger a serious crisis by 2029.

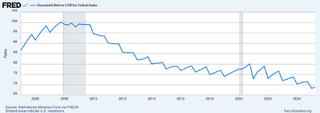

However, the analysis points out two reasons for optimism, which may bring some optimism to the current situation. First, despite the high debt/GDP ratio, the financial situation of American households is not that bad.

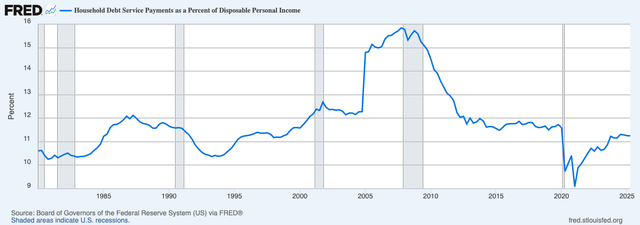

In fact, since 2008, the deleveraging process has progressed significantly and is continuing. Household debt was as high as 100% of GDP during the financial crisis; now it is only 70%. The same goes for household debt service ratios.

At least the current situation of American families is very different from 2008. At the time, debt was eating up a large portion of income, and the debt ratio of the average household was too high. Therefore, even if the crisis breaks out again in 2029, analysts believe that its impact on American households will not be as huge as the financial crisis back then. Second, rising debt and the snowball effect of interest are not unique to the US; they are a global issue.

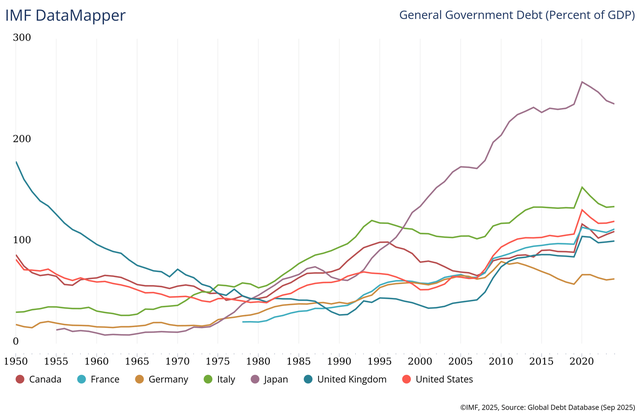

With the exception of Germany, other major economies are facing triple-digit debt and rising long-term interest rates. More precisely, countries like Japan and Italy are likely to face more complex challenges because they have higher debt and GDP growth is less rapid than America's. France is in the midst of political turmoil. Germany's GDP growth stalled two years ago, while the UK is still suffering from high inflation, and its debt/GDP ratio is as high as three digits.

In other words, it is reasonable for people to be concerned about the direction of development in the US, and the rest of the world is not optimistic. This may provide a hint of comfort; if the world faces the same problems, it may be easier to find solutions.

What are the possible solutions?

As for possible solutions, there is only one path: either the government increases cash inflows (raises taxes) or reduces cash outflows (cuts in fiscal spending). As long as spending continues to far exceed income, debt as a share of GDP cannot be improved. The truth is obvious.

However, Dario proposed a mixed approach: the best solution was to properly combine measures to suppress the economy with measures to stimulate the economy — calling it “clever deleveraging”: if taxes were raised or spending cut, it would depress the economy. However, if monetary policy is relaxed at the same time (stimulating the economy), the two can balance each other. They can both reduce the debt-to-income ratio, and they can cancel each other out. This is a carefully designed strategy.

Dario added that, as happened between 1992 and 1998, the economy can eventually find balance through “clever deleveraging” by combining austerity fiscal policies with expansionary monetary policies. In other words, if taxes and interest rates are raised, it will lay the risk of a recession; but if taxes are raised and more incentives to borrow are provided, the economy can both grow and reduce the debt burden.

Despite widespread pessimism, global debt can still be restored to sustainable levels if appropriate measures are taken.

As can be seen from this chart, this is not the first time that major economies have needed to cut fiscal deficits: this also happened after World War II. After World War II, Britain's debt/GDP ratio was once close to 200%, but after decades of hard work, this ratio was drastically reduced.

Returning to the US economy, Dario believes that the fiscal deficit should not exceed 3% of GDP. This is the upper limit, but the US economy is used to deficits of 5% to 6%. If the US begins to seriously reduce its fiscal deficit, there is still time to avoid an inevitable debt crisis.

What if the 3% threshold isn't reached?

So the question now is: Who is responsible for cutting fiscal spending or increasing taxes? This is the key to impeding economic recovery. Although Dario's idea of “clever deleveraging” can be implemented, at the same time, it is questionable whether a 3% leverage ratio can be achieved in the short term. If any politician promises to raise taxes and cut spending, can they still be elected? It all starts with the will of people to sacrifice the present for a better future. This path is bound to be no easy one, but the problem of procrastination itself is a choice, and this choice is bound to have consequences. Avoiding a problem won't make it go away.

In response, Dario said, “This is reality because it will trigger an open conflict, and it's likely not going to happen. But if you don't do it, you're in trouble. So this is an option. If you don't do it, take responsibility. Tell yourself that if you don't do it, the crisis I'm talking about will come, and I can't tell you exactly when it will. It's like a heart attack; you can't predict it accurately, right? I understand you're getting closer. I think it's about three years, floating up and down for a year.”

Just like people with serious cardiovascular disease, if they continue to have an unhealthy lifestyle, sooner or later they will have a heart attack. However, heart attacks can't be predicted, and so is the US debt crisis. Dario seems pretty sure that the crisis will break out in 2029. You can't wait until a crisis hits to enter the market: the potential gains you give up may be higher than the potential losses you might face.

Dario believes that the US is currently approaching a period of major changes in the monetary system, and its impact is comparable to the Nixon shock (August 15, 1971).

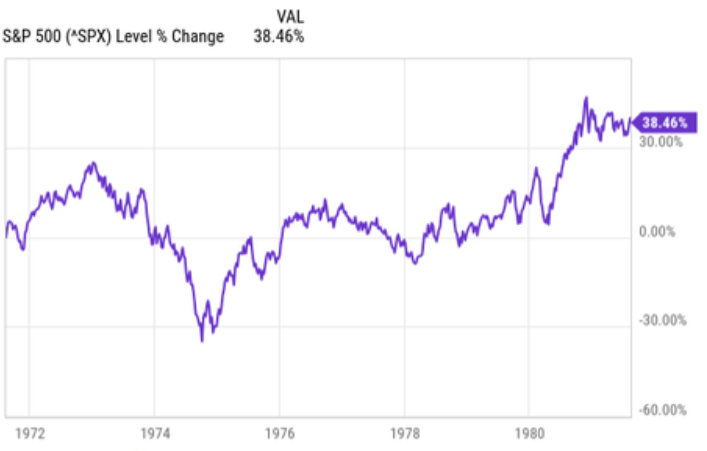

From 1974 to the beginning of 1980, the overall performance of the stock market was poor, but this was not the end of the world; on the contrary, it was a period full of opportunities. However, in the long run, US stocks have doubled several times over the past few decades.

Overall, Dario's point may make sense, but that doesn't mean you shouldn't invest. Adopting a “wait and see” strategy forever will never pay off. No one knows if changes in the monetary system will occur, and if they do, the timing may not be right.

What does a “debt heart disease” attack look like?

What would it be like if the economy could no longer avoid a debt crisis? Dario believes this will be different from the Nixon shock. What is certain to happen is that the Federal Reserve will buy bonds as much as before. It won't necessarily make announcements, but it will launch like 2008 or 2020, only on a larger scale. To deal with this situation, as in 1971, measures may be taken, such as extending the term of the debt. These are all possible.

Dario said, “Therefore, don't expect the Federal Reserve to issue an official statement clearly explaining the unsustainability of US debt, but more likely to take a more obscure approach. When interest rates on debt become too heavy and demand for US Treasury bonds falls, the Federal Reserve will begin large-scale purchases of already issued treasury bonds. Also, the Federal Reserve may extend the term of the debt, and I think this is more likely if the inflation rate exceeds the 2% target.”

Dario also pointed out another option, although this one is the least likely: not paying the debt through various excuses.

Dario explained, “We live in a world similar to the 1930s. For example, the US froze the assets of Japanese people in the 1930s, that is, we froze their bonds, which means they can't get the money. So now, due to sanctions, debt backlogs, etc., when I calculate who is the buyer and how many bonds we need to sell, I see a serious imbalance between supply and demand, and I know what's going on. In other words, this is a hidden breach of contract. However, this is a hopeless act, and there is currently zero chance of it happening. We still have time to reverse our debt problem; we only need to reach the 3% threshold mentioned earlier.”

Why should we focus on Dario's theory?

In addition to his extensive knowledge of economic history, the reason why his arguments are worth paying attention to is also related to our experience in 2025 — he accurately predicted the environment for the remaining nine months of this year in March. Dario said, “The situation on that day looked like it happened on August 15, 1971, only on a larger scale. You'll see supply and demand issues. You'll see interest rates soaring and currency tightening, just like what happened in 2020. Interest rates will soar. This will be reflected in rising interest rates and falling currency values, particularly relative to gold or other currencies. Perhaps, although this will affect all currencies, as they will depreciate, you will see interest rates rise even if the Federal Reserve adopts an easing policy. Then you'll see the Fed take another step, buy assets and implement a new round of quantitative easing, and then you'll see a reaction similar to 2021 and 2020. Not only will inflation, but the price of gold and other related assets will also rise.”

This is mostly true. This year, the US dollar will depreciate against major foreign currencies and gold. Even if the federal funds rate falls, market interest rates will rise. US 30-year Treasury yields have risen, but US 10-year Treasury yields have remained unchanged. Despite the Federal Reserve's interest rate cut, long-term bond yields are still very high, which shows that bond market observers are not optimistic about US Treasury bonds.

The final prediction is that the Federal Reserve will once again introduce quantitative easing. This month, the Federal Reserve announced that it will restart its short-term treasury bill purchase program, purchasing at least 40 billion US dollars a month, and will continue until at least April. Although the official purpose of this move is to balance the bank buyback market and is not strictly quantitative easing, it highlights the Federal Reserve's intention to adopt a more relaxed monetary policy in the next few months.

Overall, the picture Dario described in March 2025 is gradually taking shape over time: betting on 2026 depreciation doesn't seem that far off.

Nasdaq

Nasdaq 華爾街日報

華爾街日報